ECI failed to verify SIR draft rolls as thousands of voters vanish in Tamil Nadu

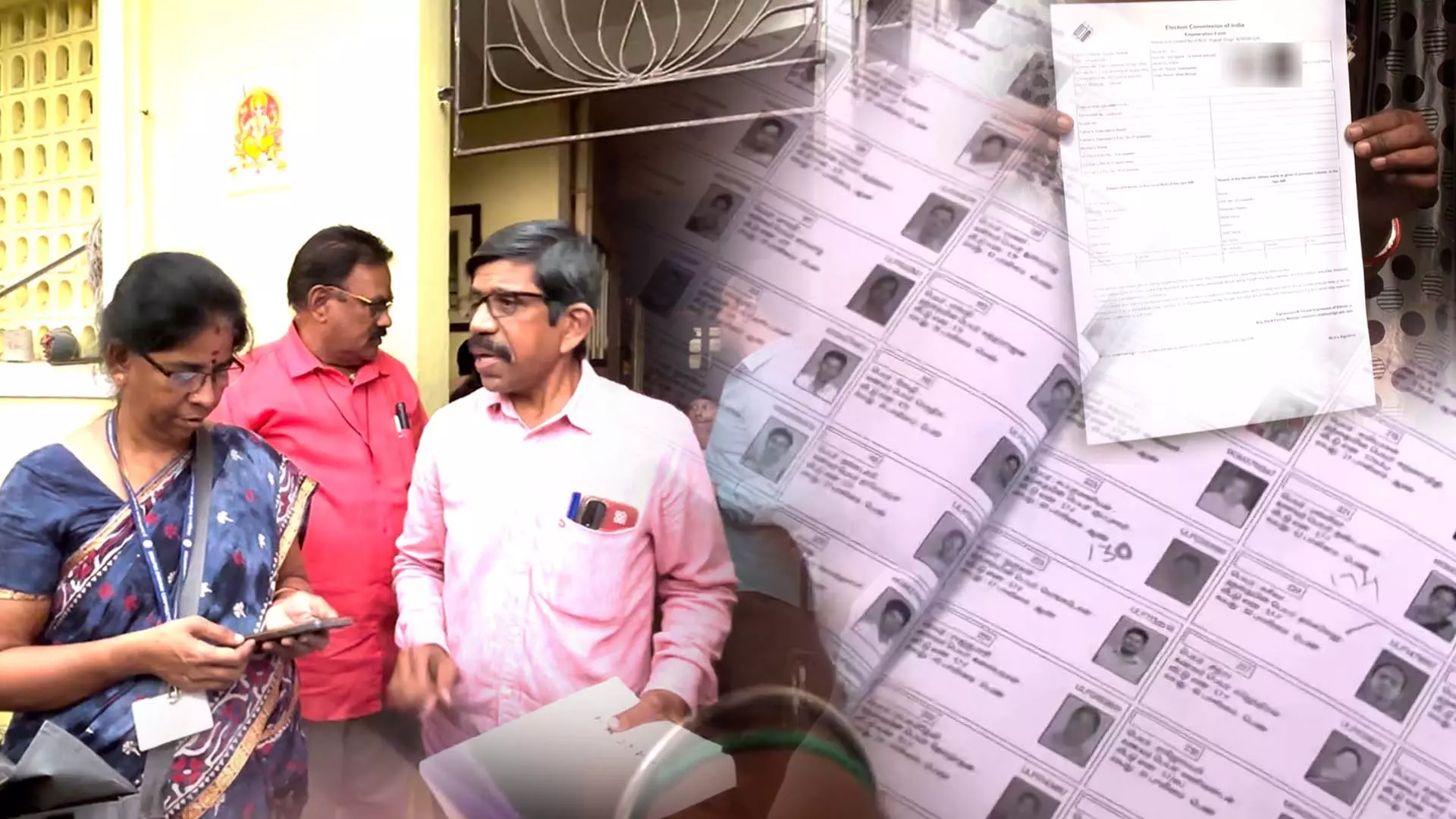

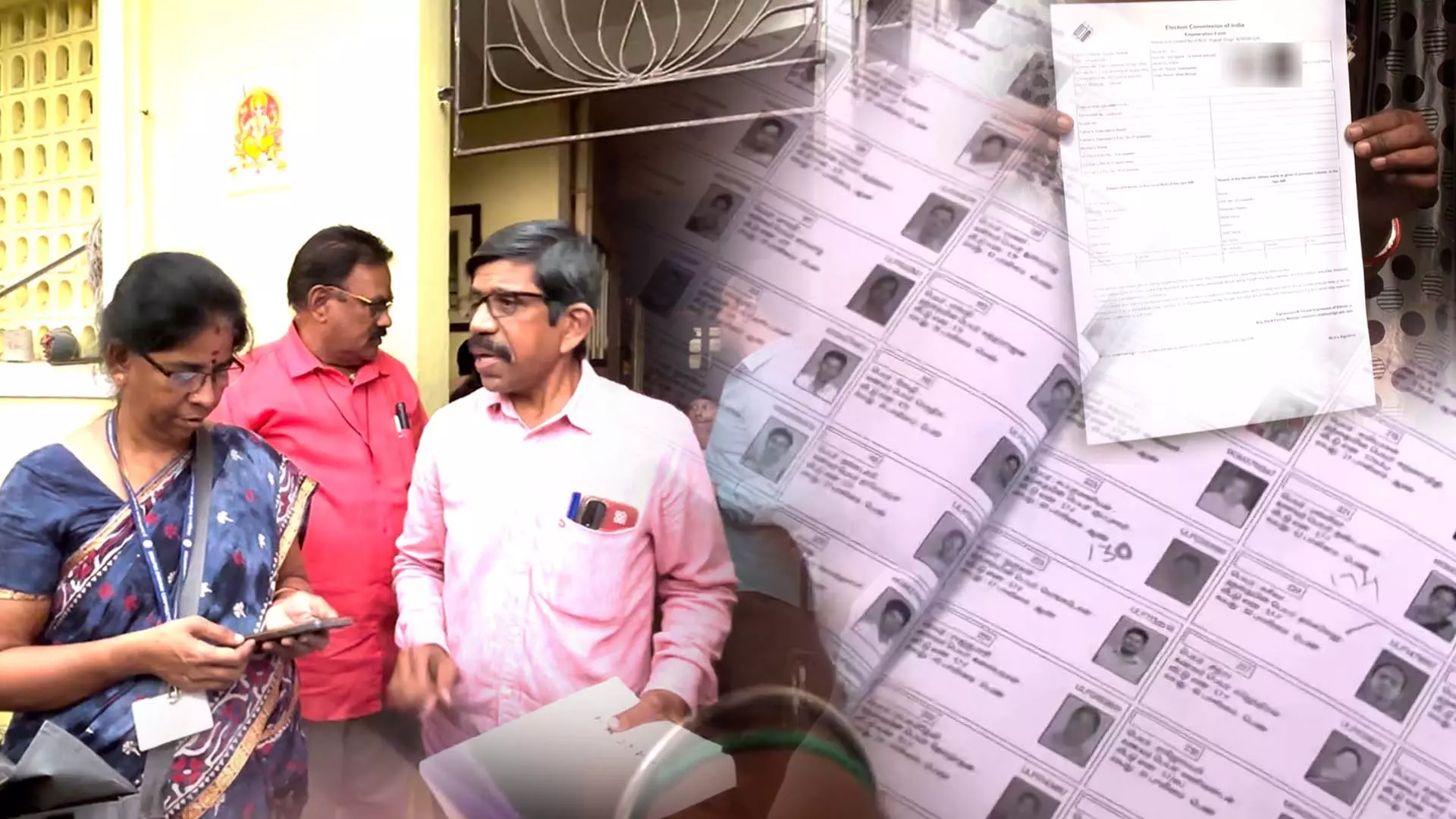

ECI failed to ensure basic verification during the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Tamil Nadu, leading to large-scale deletions that have raised serious concerns about the credibility of the process. The latest draft rolls show living voters marked as “deceased,” entire neighbourhoods removed in bulk, and eligible electors left unaware that their names no longer exist on voter lists.

The issue is not limited to isolated cases. Field visits and data analysis reveal a pattern of sweeping deletions carried out without adequate checks. Voters who had appeared in previous electoral rolls, and even participated in recent elections, were suddenly removed during the SIR exercise.

In a small hamlet under the Tirumangalam constituency near Madurai, draft rolls showed 77 people listed as dead within a single year. Shockingly, 47 of them were below the age of 40. Ground verification revealed that many of them were alive and residing in the same location. Entire sequences of voters, listed consecutively in earlier rolls, were deleted in one stroke.

This booth alone saw 128 deletions, with 123 marked as deceased. The improbability of such a demographic event highlights the absence of even basic scrutiny before releasing the draft.

ECI failed as consecutive voter blocks were deleted without scrutiny

An analysis of deletions across districts indicates that this was not an administrative error limited to one region. At least 57 instances were identified where 50 or more voters, listed consecutively in earlier rolls, were removed together. Such patterns strongly suggest bulk action rather than individual verification.

In Madathukulam constituency in Tiruppur district, one rural booth saw 205 out of 276 deleted voters marked as deceased. More than half of them were under the age of 50. Overall, 35.6% of the booth’s voters disappeared from the draft rolls. Officials admitted that they lacked the tools and time to flag such anomalies before publication.

Statewide, nearly 97.4 lakh electors were dropped in the SIR draft. Despite this massive figure, there appears to have been no system-level audit to detect irregular trends like unusually high death markings or sudden mass removals in specific booths.

Officials at various levels acknowledged that many of those deleted are now submitting Form 6 applications for re-inclusion. However, this correction process depends entirely on voter awareness, which remains alarmingly low in many areas.

ECI failed voters as awareness gaps left many excluded

In urban areas like Vadapalani in Chennai, a single booth recorded 802 deletions from a voter base of 1,312. Records show that 753 people from the same booth had voted in the 2024 Lok Sabha election. The numbers simply do not add up.

On Bhajanai Koil Second Street alone, 332 out of 485 voters were removed. Several residents said they were unaware that the SIR process was even underway. Couples who had lived in the same houses for decades were marked as “shifted” or “absent.” Some were marked deceased while standing very much alive in front of officials.

Similar patterns emerged in Egmore, where nearly half the voters in a booth were deleted. Even households that submitted enumeration forms were removed, raising questions about whether field data was properly recorded or reviewed.

View this post on Instagram

What makes the situation more troubling is that while genuine residents were deleted, some voters who had actually shifted residences continued to remain on the rolls. This points to random and inconsistent application of deletion criteria.

Many officials privately admitted that the rushed timeline of the SIR exercise led to unintended consequences. But unintended or not, the responsibility lies squarely with the system that released unchecked draft rolls impacting millions. Also Read: Doctor Booked in Tamil Nadu After Court-Ordered Hospital Demolition Move in 2026

Conclusion

ECI failed to uphold the integrity of voter verification during the SIR process in Tamil Nadu. The scale and pattern of errors suggest systemic weaknesses rather than isolated mistakes. As corrections continue, the real concern remains whether all affected voters will even realise they were deleted before final rolls are published. The credibility of the electoral process depends not on corrections after damage, but on accuracy before publication.