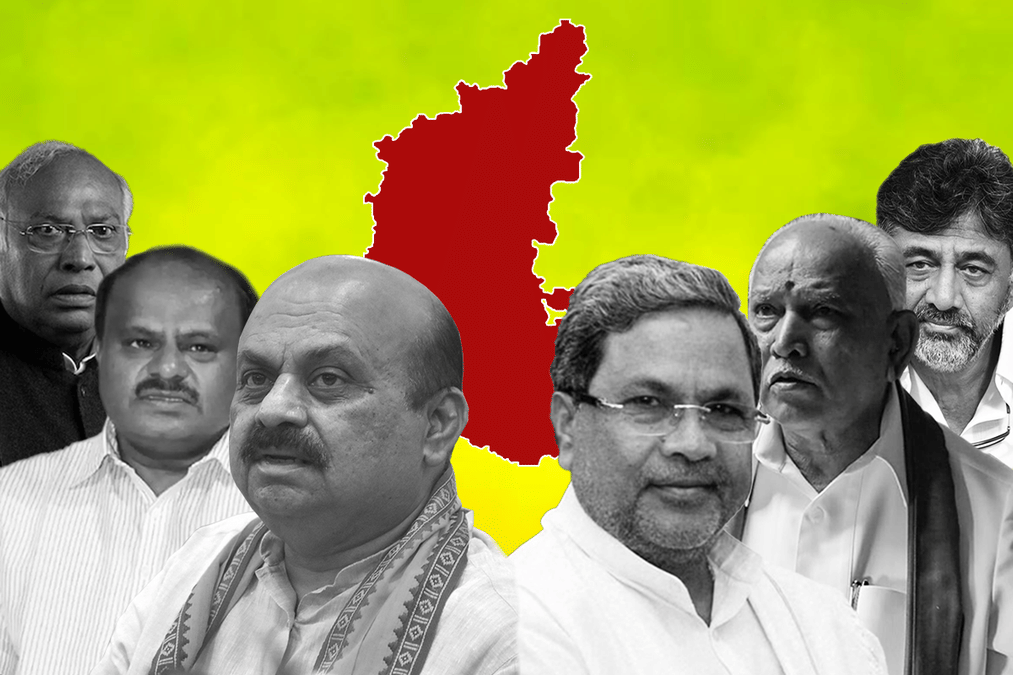

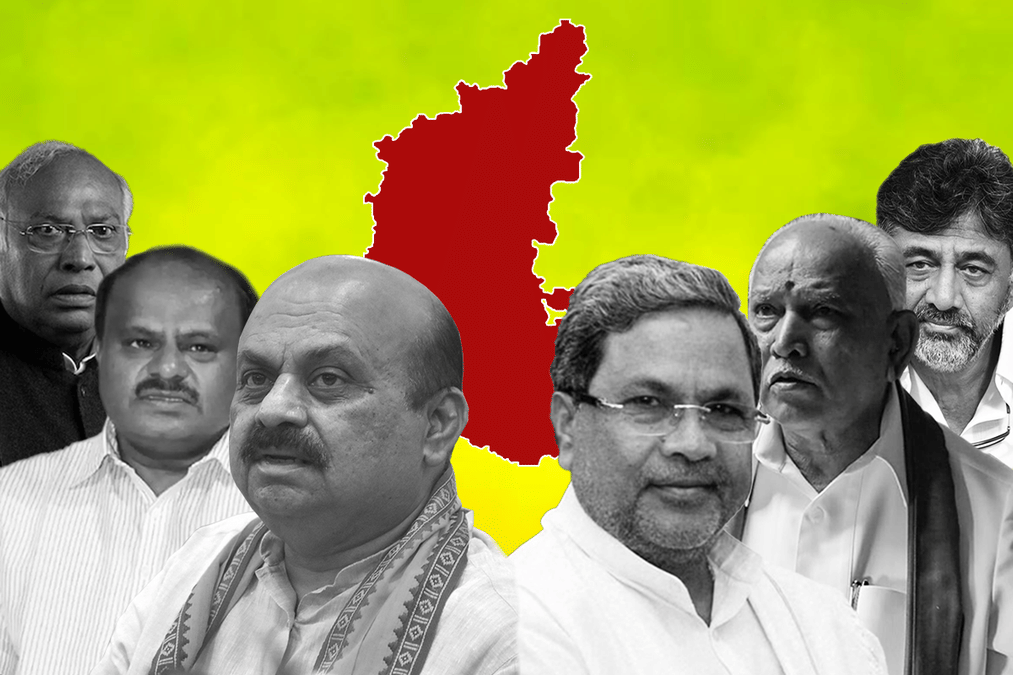

A fresh controversy has emerged in Karnataka as a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) delegation formally appealed to the Backward Classes (BC) Commission to exclude Christian sub-castes from its ongoing community survey. The delegation argued that including Christian groups in the survey of backward classes was unjustified, claiming that it could distort existing reservation policies. According to them, the commission’s mandate should focus solely on Hindu backward classes, as the inclusion of Christian sub-castes could alter social justice frameworks.

The demand sparked immediate political reactions, with opposition leaders accusing the BJP of playing divisive politics. They contended that the delegation’s request undermines the principles of inclusivity and equal representation. The debate has now brought renewed attention to caste-based surveys in Karnataka, which have long been contentious due to their impact on reservation policies, resource allocation, and community identities. The issue is expected to generate further political clashes as the state government decides on how to handle the request.

The BJP leaders presented their memorandum to the BC Commission, asserting that caste distinctions within Christianity were a matter of religious adaptation and should not be given the same recognition as Hindu backward classes. They maintained that extending such recognition could lead to unnecessary expansion of reservation benefits, diluting the opportunities available to traditional backward class communities.

Their demand also drew on the argument that Christianity, as a faith, emphasizes equality and does not support caste hierarchies, making the inclusion of sub-castes contradictory. Critics, however, countered that in practice, caste divisions do persist within Christian communities, influencing access to education, employment, and social mobility. Activists pointed out that ignoring these realities would mean neglecting vulnerable groups who continue to face discrimination despite religious conversion. This clash of perspectives has intensified Karnataka’s already heated debates on reservation and caste-based representation.

The issue also carries broader political implications. The timing of the BJP’s demand is significant, as caste surveys have become a central political issue in Karnataka ahead of upcoming elections. Observers believe the party is attempting to consolidate its traditional vote base by resisting changes that could shift reservation benefits toward minority groups. Meanwhile, the ruling government is under pressure to balance competing demands: ensuring fairness for backward classes while upholding the rights of minorities.

The BC Commission has yet to announce its decision, but its response could influence voter sentiment and community relations across the state. The controversy has also drawn attention from national political circles, where caste surveys and minority rights remain deeply polarizing topics. For many, the outcome will be a test of Karnataka’s ability to navigate sensitive social questions without deepening divisions. The lessons from this episode could resonate far beyond the state, shaping broader debates on caste, religion, and representation in India’s democracy.

Clash Between Representation and Identity Politics

The demand to exclude Christian sub-castes has reopened questions about the very purpose of caste surveys. While some argue that surveys should reflect social realities across all communities, others believe they should focus on historically disadvantaged groups within Hindu society. The BJP delegation’s stance leans toward the latter, framing the issue as one of protecting the rights of Hindu backward classes.

Opponents, however, argue that such exclusion is arbitrary and discriminatory, especially when evidence suggests caste-based disadvantages persist among Christians as well. They fear that ignoring these groups will perpetuate social inequalities. Activists insist that a true backward class survey must be inclusive, reflecting the lived experiences of all marginalized communities. The BC Commission now faces the delicate task of balancing these competing viewpoints while ensuring the integrity of the survey. Its decision will likely have lasting consequences on Karnataka’s social justice policies.

The controversy has also sparked debate about the intersection of religion and caste in India. Christianity, in principle, preaches equality and brotherhood, but caste hierarchies have historically persisted among Indian converts. Scholars argue that conversion did not erase centuries-old social divisions, and many sub-castes continue to exist within Christian communities, affecting marriage, occupation, and access to opportunities.

Ignoring these distinctions, they say, risks erasing the struggles of marginalized Christian groups. The BJP, however, maintains that extending caste recognition to Christians undermines the unique historical basis of reservation for Hindu backward classes. This ideological divide underscores a broader tension in Indian society: how to reconcile religious equality with the persistence of caste realities. The Karnataka case could set a precedent for how other states handle similar issues, making the BC Commission’s decision particularly significant.

Political Stakes and Social Consequences

At its core, the BJP delegation’s demand represents a political gamble aimed at consolidating its support among traditional backward classes. By opposing the inclusion of Christian sub-castes, the party is signaling that it seeks to safeguard the interests of Hindu communities that form a large part of its voter base. Critics, however, see this as a divisive tactic designed to marginalize minorities for electoral gain.

The Congress and other opposition parties have accused the BJP of undermining Karnataka’s pluralistic values. Civil society organizations, too, have warned that excluding Christian sub-castes could lead to heightened tensions between communities, weakening the state’s social harmony. As debates intensify, the BC Commission’s response will be closely scrutinized for its potential to influence not just policy but also the political climate ahead of elections. For now, the controversy highlights how deeply caste and religion remain intertwined in Karnataka’s social and political fabric.

The BJP’s demand to exclude Christian sub-castes from the BC Commission’s survey has reignited longstanding debates over reservation in Karnataka. For decades, the question of who qualifies as backward has divided political parties, academics, and communities. The current controversy is yet another reminder of the sensitive balance between ensuring social justice and avoiding political polarization. Reservation has always been a contested subject, as different groups compete for limited resources and opportunities. By seeking to exclude Christian sub-castes, the BJP has introduced an additional layer of complexity that could reshape the state’s social justice policies.

The commission’s survey itself has been a matter of intense scrutiny, with various communities lobbying for inclusion or greater recognition. The addition or removal of any group has implications not only for resource allocation but also for political representation. By targeting Christian sub-castes, the BJP delegation is attempting to draw clear boundaries between minority and majority communities in the context of backward class rights. However, such distinctions are not easy to enforce, given the historical and social realities of caste that transcend religious boundaries. Critics argue that selective recognition undermines the credibility of the survey.

Legal experts have also weighed in on the controversy, pointing out that excluding Christian sub-castes could raise constitutional questions. India’s Constitution guarantees equality and prohibits discrimination based on religion. If caste-based discrimination continues to exist among Christians, denying them recognition could violate principles of fairness and justice. Courts have previously ruled in favor of including marginalized groups, irrespective of their faith, if social and economic backwardness could be demonstrated. The commission’s decision, therefore, must align with both legal precedent and constitutional values.

The debate has also drawn attention to the lived realities of marginalized Christians in Karnataka. Activists highlight that despite conversion, many Dalit Christians continue to face exclusion, both socially and economically. They are often denied opportunities, stigmatized in their communities, and restricted in their upward mobility. For them, recognition in the BC survey is not just symbolic but essential for accessing educational and employment opportunities. Denying this recognition, they argue, would amount to erasing their struggles. This perspective challenges the narrative that conversion alone guarantees equality.

On the other hand, the BJP has framed its demand as a defense of Hindu backward classes who, it argues, risk being sidelined if the survey includes too many groups. Party leaders have stated that the intent is not to attack minorities but to protect existing reservation benefits. They contend that the expansion of the list dilutes the share of resources available to historically disadvantaged Hindu communities. By presenting the issue in this manner, the BJP hopes to reassure its core voter base while deflecting accusations of discrimination.

The ruling government finds itself in a difficult position, caught between conflicting demands. On one side are groups demanding inclusivity and recognition, while on the other are political pressures to protect established backward classes. Any decision could have significant electoral consequences, as caste and community identities play a central role in Karnataka’s politics. The government has so far remained cautious, emphasizing that the commission will decide based on evidence and legal frameworks. However, behind the scenes, leaders are acutely aware of the risks of alienating either majority or minority groups.

Observers note that the controversy is also part of a larger national debate on the intersection of caste and religion. Similar issues have emerged in other states, where Christian and Muslim backward communities have sought recognition. The outcome in Karnataka could therefore set a precedent with implications far beyond the state. If the BC Commission decides to exclude Christian sub-castes, it may embolden similar demands elsewhere. Conversely, if it includes them, it could encourage other marginalized minority groups to push for recognition. Either way, the impact will be felt nationally.

Civil society groups have urged the commission to focus on data rather than politics. They argue that the survey’s primary purpose is to provide an accurate picture of social and economic realities. Excluding communities for political reasons, they warn, risks undermining the credibility of the entire exercise. Such an outcome would not only weaken the survey but also erode public trust in institutions meant to promote social justice. Activists stress that the integrity of the process must be protected above all else, even if it means facing political backlash.

Follow: Karnataka Government

Also read: Home | Channel 6 Network – Latest News, Breaking Updates: Politics, Business, Tech & More