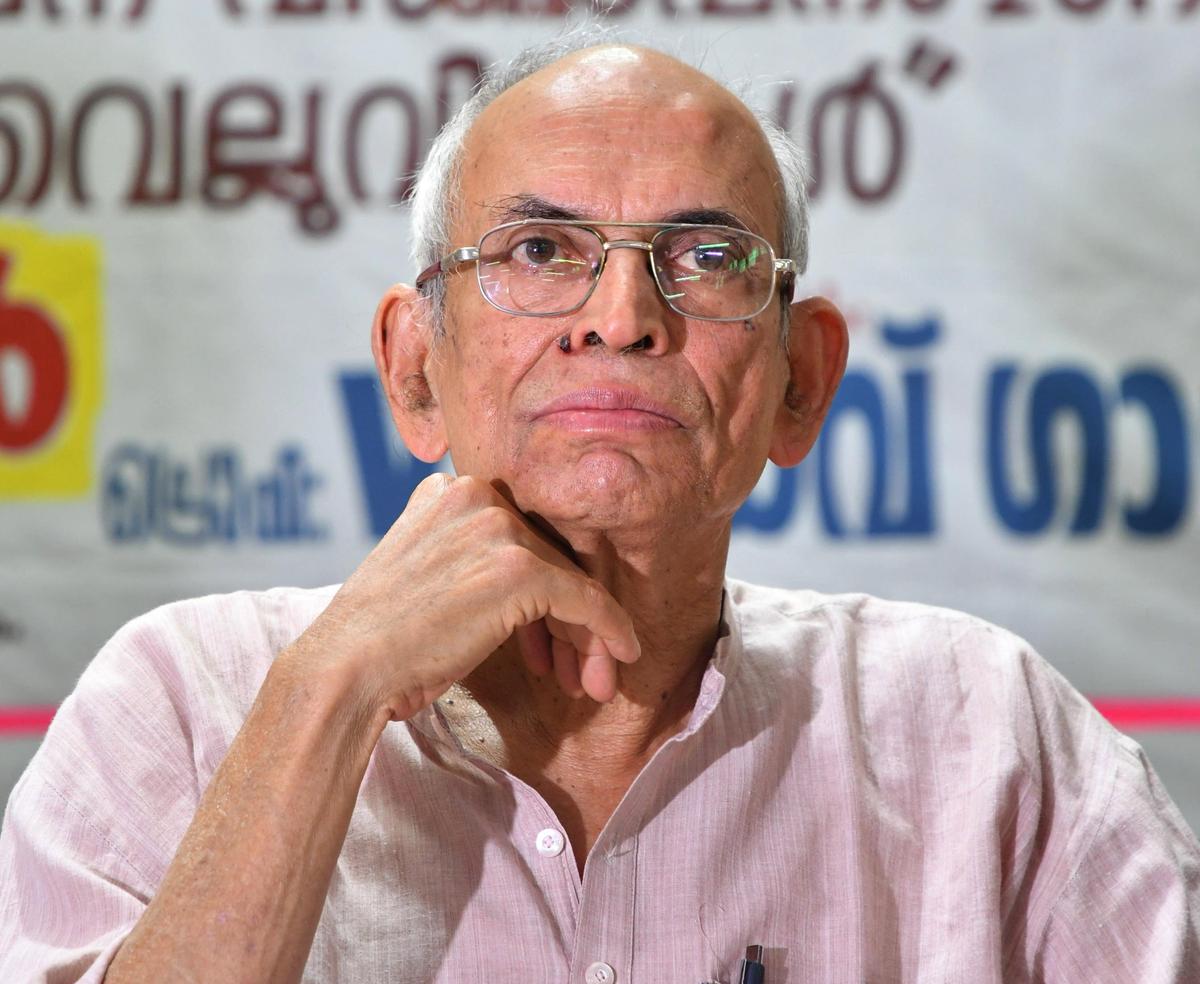

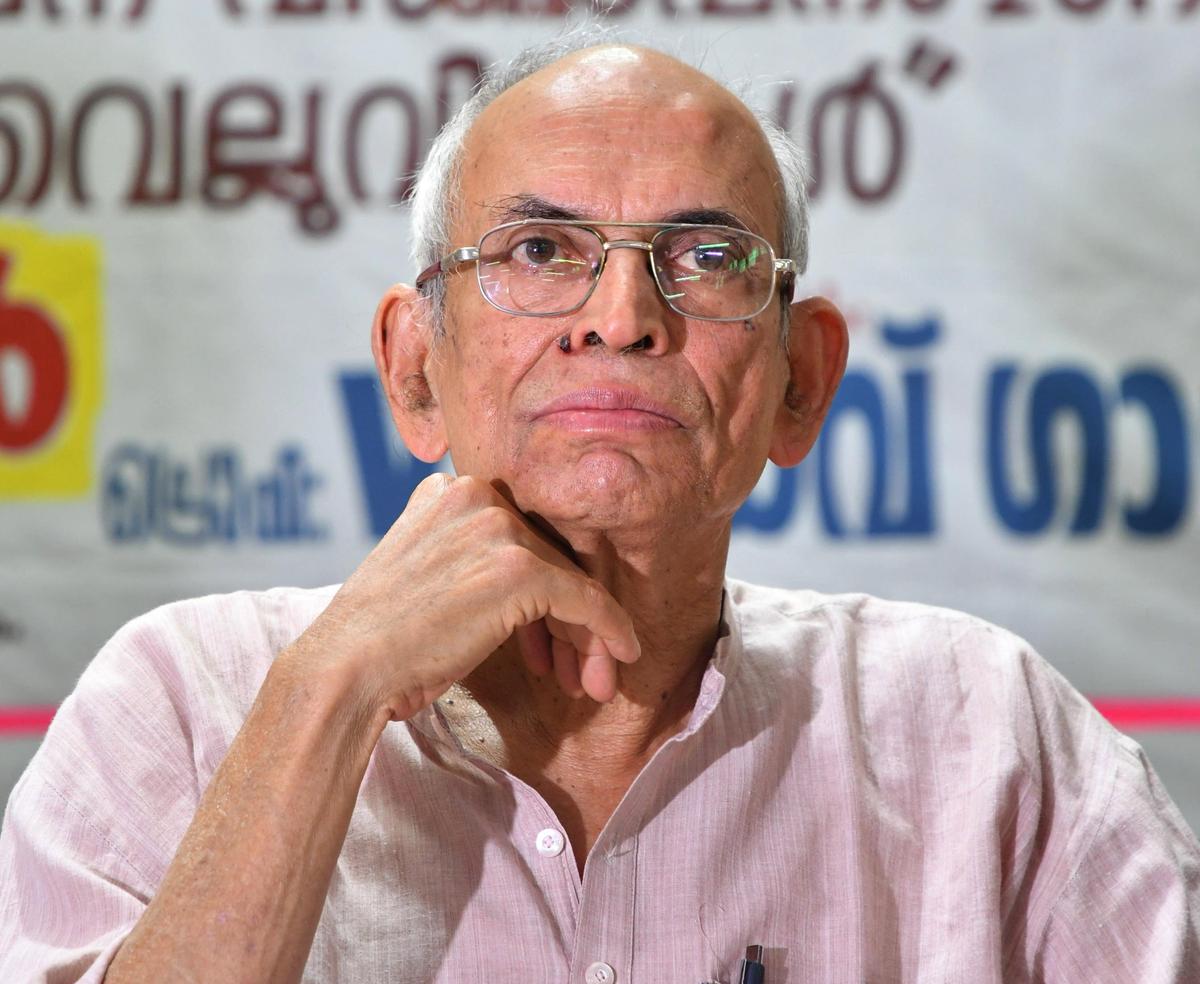

Madhav Gadgil’s association with Karnataka was not confined to a single role, institution, or movement. It spanned more than five decades, cutting across academia, environmental governance, public policy, and grassroots engagement. From heading the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel to playing a key role in shaping world-class research centres at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, Gadgil’s influence on the State’s intellectual and ecological landscape remains profound. Revered by conservationists, debated by policymakers, and remembered fondly by generations of students, Gadgil’s Karnataka years reflect a life devoted to knowledge, ethics, and ecological responsibility.

Born in 1942 into a family deeply rooted in scholarship and public service, Gadgil brought to Karnataka not only his scientific expertise but also a distinctive philosophy that blended rigorous research with democratic participation. His work consistently challenged the idea that conservation must be imposed from above, instead arguing for people-centred environmental governance. Karnataka became both the laboratory and the proving ground for these ideas, shaping his work and, in turn, being shaped by it.

Gadgil first came to prominence in Karnataka through his long association with the Indian Institute of Science, where he served as a professor and later played a pivotal role in establishing interdisciplinary research initiatives. IISc, already a premier institution, found in Gadgil a scholar who pushed boundaries, encouraging collaborations between ecology, sociology, economics, and public policy. His presence at IISc coincided with a period when environmental science was gaining urgency, and he ensured that Karnataka stood at the forefront of this intellectual shift.

At IISc, Gadgil was instrumental in nurturing centres that went on to achieve international recognition. He believed that ecological research should not remain confined to academic journals but must inform governance and public debate. This belief shaped the ethos of several programmes he helped establish, many of which trained researchers who later became influential voices in conservation across India. For Gadgil, Karnataka was not just a workplace but a space where ideas could mature into action.

Beyond institutional walls, Gadgil engaged deeply with Karnataka’s landscapes. His research on biodiversity, community-managed forests, and traditional ecological knowledge drew extensively from regions within the State. He spent years studying the intricate relationships between local communities and natural resources, particularly in forested and semi-forested regions. These studies laid the foundation for his later work on participatory conservation, a concept that would define his legacy.

Gadgil’s philosophy stood in contrast to command-and-control models of environmental regulation. He argued that conservation imposed without local consent was both unjust and ineffective. Karnataka’s diverse socio-ecological settings, from the Western Ghats to the Deccan plateau, provided him with real-world examples of how decentralised decision-making could work. Village-level forest management practices, traditional water harvesting systems, and community norms all featured prominently in his writings and teaching.

WESTERN GHATS PANEL AND A CONTROVERSIAL TURN

Gadgil’s most publicly visible role came in 2010, when he was appointed chairperson of the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel. Tasked with assessing the ecological sensitivity of the Western Ghats, the panel’s mandate was ambitious and politically sensitive. The Western Ghats stretch across six States, but Karnataka, with its extensive Ghats region, was central to the panel’s work. Gadgil approached the task with characteristic thoroughness, grounding recommendations in scientific data while emphasising community participation.

The panel’s report, submitted in 2011, classified the Western Ghats into different ecological sensitivity zones and recommended restrictions on environmentally destructive activities in the most fragile areas. In Karnataka, conservationists welcomed the report as a long-overdue corrective to unregulated mining, deforestation, and infrastructure expansion. Many hailed Gadgil for articulating what scientists had warned about for decades: that unchecked development in the Ghats could have irreversible consequences.

However, the reaction from sections of the public and political establishment was sharply divided. In the foothills of the Western Ghats, especially in parts of Karnataka, farmers, plantation owners, and local residents expressed fear that the recommendations would threaten livelihoods and land rights. The report was portrayed by critics as anti-development, despite Gadgil’s insistence that sustainable livelihoods were central to his vision.

As Karnataka navigates the challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, and sustainable development, Gadgil’s ideas remain strikingly relevant. His insistence on participatory governance, respect for local knowledge, and ethical restraint offers a framework that goes beyond policy prescriptions. It calls for a reimagining of progress itself.

More than a scientist or administrator, Madhav Gadgil was a public intellectual whose long association with Karnataka helped define the State’s environmental conscience. His work reminds us that true development lies not in conquering nature, but in learning to live within its limits, a lesson Karnataka continues to grapple with, decades after he first articulated it.

Public consultations became arenas of tension. Gadgil, known for his calm demeanour and willingness to engage, attended meetings where emotions ran high. He repeatedly clarified that the panel did not advocate blanket bans but sought context-specific regulations shaped by local voices. Yet, misinformation and political mobilisation often drowned out these nuances. Karnataka became one of the epicentres of the Gadgil report controversy, shaping public discourse on conservation for years to come.

The State government eventually distanced itself from the report, favouring a more diluted framework proposed by a subsequent committee. For Gadgil, this outcome was disappointing but not entirely unexpected. He later remarked that resistance to ecological regulation often stemmed from a failure to involve communities meaningfully from the outset. Despite the setback, the report left an indelible mark, ensuring that the Western Ghats would remain central to environmental debates in Karnataka.

Importantly, the controversy did not diminish Gadgil’s standing among Karnataka’s conservationists. Many viewed his work as a moral benchmark, a document that spoke truth to power even if it was politically inconvenient. Environmental movements across the State continued to cite the report, drawing on its scientific credibility to challenge environmentally harmful projects.

IISc, PUBLIC INTELLECTUALISM, AND LASTING INFLUENCE

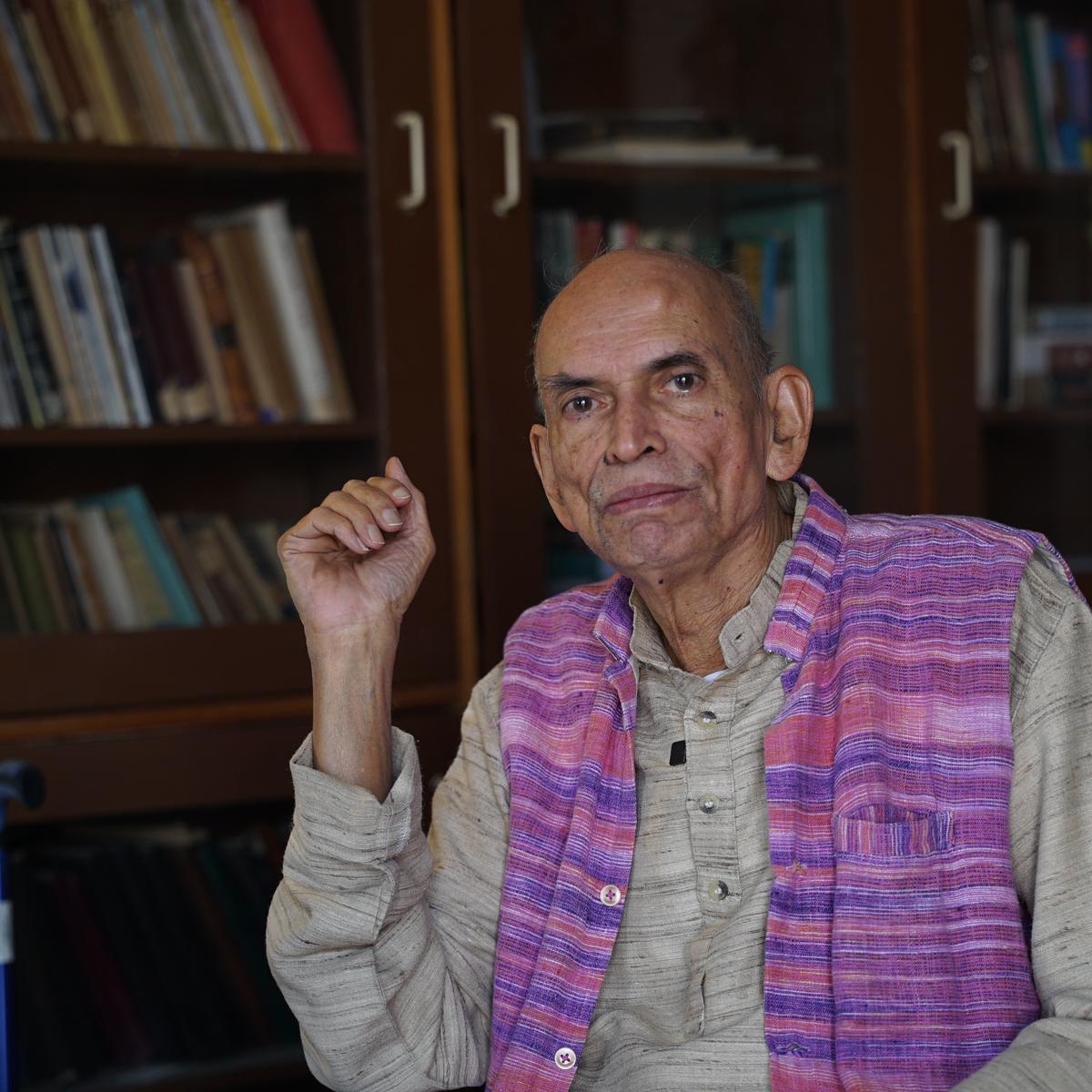

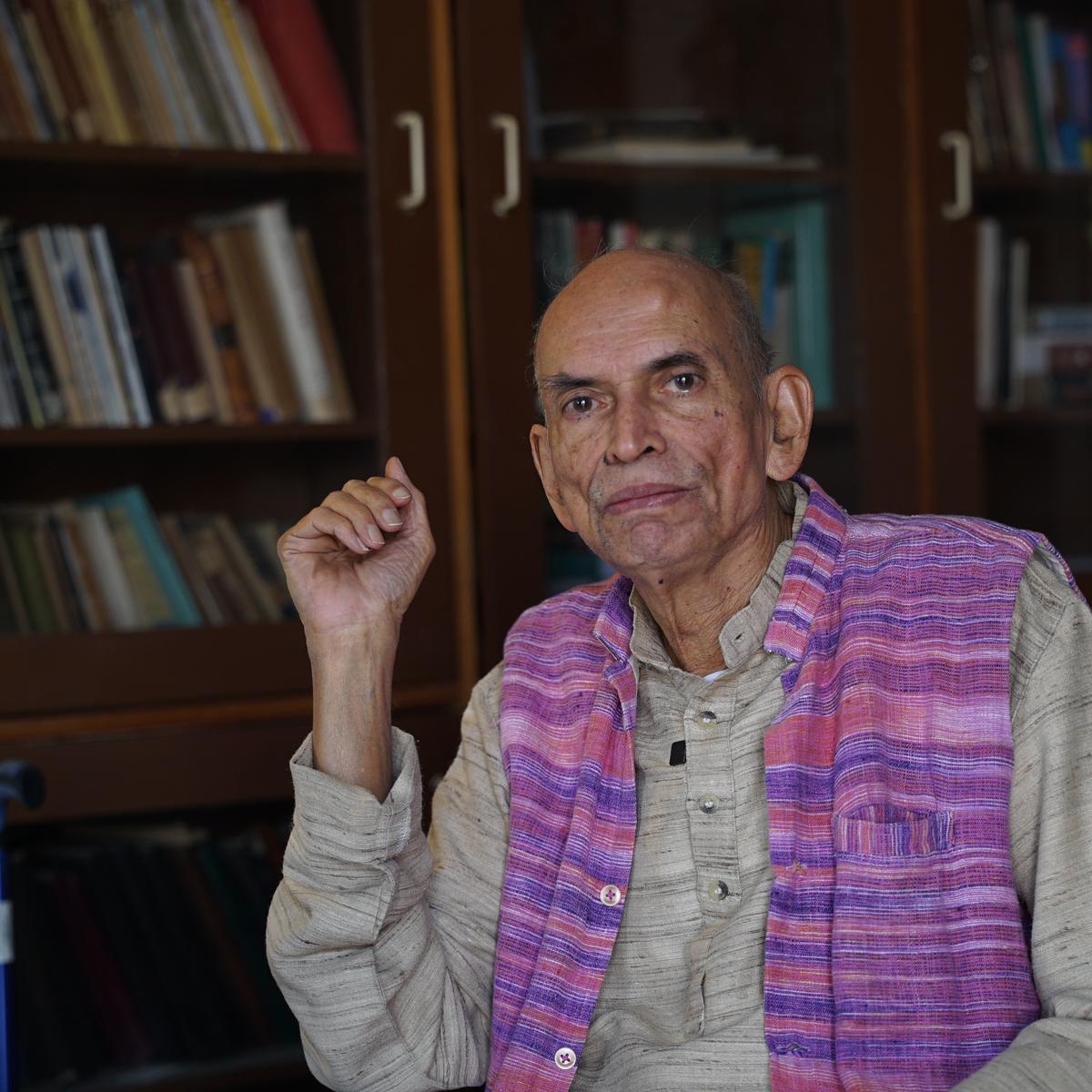

While the Western Ghats panel brought Gadgil into the national spotlight, his quieter, sustained contributions within Karnataka arguably had a deeper impact. At IISc, he championed the idea of universities as public institutions with responsibilities beyond teaching and research. He encouraged students and colleagues to engage with society, write in regional languages, and participate in public debates.

Gadgil’s efforts to bridge the gap between science and policy found fertile ground in Karnataka. He collaborated with State agencies, civil society organisations, and grassroots groups, offering expertise without compromising his independence. His involvement in biodiversity documentation initiatives helped Karnataka become one of the States with the most comprehensive records of flora and fauna, a crucial tool for conservation planning.

Equally significant was Gadgil’s commitment to nurturing young minds. Former students recall a mentor who challenged them intellectually while instilling humility and ethical responsibility. He encouraged questioning, discouraged blind adherence to authority, and emphasised evidence-based reasoning. Many of his students went on to occupy influential positions in academia, government, and non-governmental organisations, carrying forward his ideas in varied forms.

Gadgil also played a role in shaping Karnataka’s approach to biodiversity governance through his involvement in people’s biodiversity registers. These initiatives sought to document local ecological knowledge, recognising communities as custodians of biodiversity rather than obstacles to conservation. Karnataka’s experience with such registers informed national biodiversity policies, reflecting Gadgil’s belief that local action could influence broader frameworks.

Even after formal retirement, Gadgil remained deeply engaged with Karnataka’s intellectual life. He continued to write, speak, and participate in discussions, often from his home but always with a keen awareness of developments in the State. His writings in Kannada and English reached diverse audiences, reinforcing his conviction that knowledge should be accessible and inclusive.

In the later years of his life, Gadgil increasingly reflected on the moral dimensions of science. He warned against the commodification of nature and the erosion of ethical considerations in development planning. Karnataka’s rapid urbanisation, mining pressures, and infrastructure expansion featured prominently in his critiques, not as isolated issues but as symptoms of a deeper imbalance between economic ambition and ecological limits.

Gadgil’s passing prompted an outpouring of tributes from across Karnataka. Academics remembered a rigorous scholar, activists remembered an ally, and students remembered a teacher who believed in their potential. For many, his life represented the possibility of combining scientific excellence with social commitment, a rare blend in an increasingly specialised world.

His association with Karnataka ultimately transcended institutions and controversies. It was rooted in a sustained engagement with the State’s people, landscapes, and ideas. From the classrooms of IISc to the forests of the Western Ghats, Gadgil left behind a legacy that continues to shape debates on development and conservation.

As Karnataka navigates the challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, and sustainable development, Gadgil’s ideas remain strikingly relevant. His insistence on participatory governance, respect for local knowledge, and ethical restraint offers a framework that goes beyond policy prescriptions. It calls for a reimagining of progress itself.

More than a scientist or administrator, Madhav Gadgil was a public intellectual whose long association with Karnataka helped define the State’s environmental conscience. His work reminds us that true development lies not in conquering nature, but in learning to live within its limits, a lesson Karnataka continues to grapple with, decades after he first articulated it.

Follow: Karnataka Government

Also read: Home | Channel 6 Network – Latest News, Breaking Updates: Politics, Business, Tech & More