With barely four months left for the current academic year to conclude, the State government is yet to procure sanitary pads under the Shuchi scheme, raising serious concerns about menstrual hygiene support for adolescent girls studying in government schools. The delay has triggered criticism from educationists, public health experts, and activists, who say the lapse undermines years of progress made in normalising menstrual health and ensuring dignity for school-going girls. For thousands of students who rely exclusively on the scheme, the uncertainty has translated into anxiety, absenteeism, and an erosion of trust in welfare delivery.

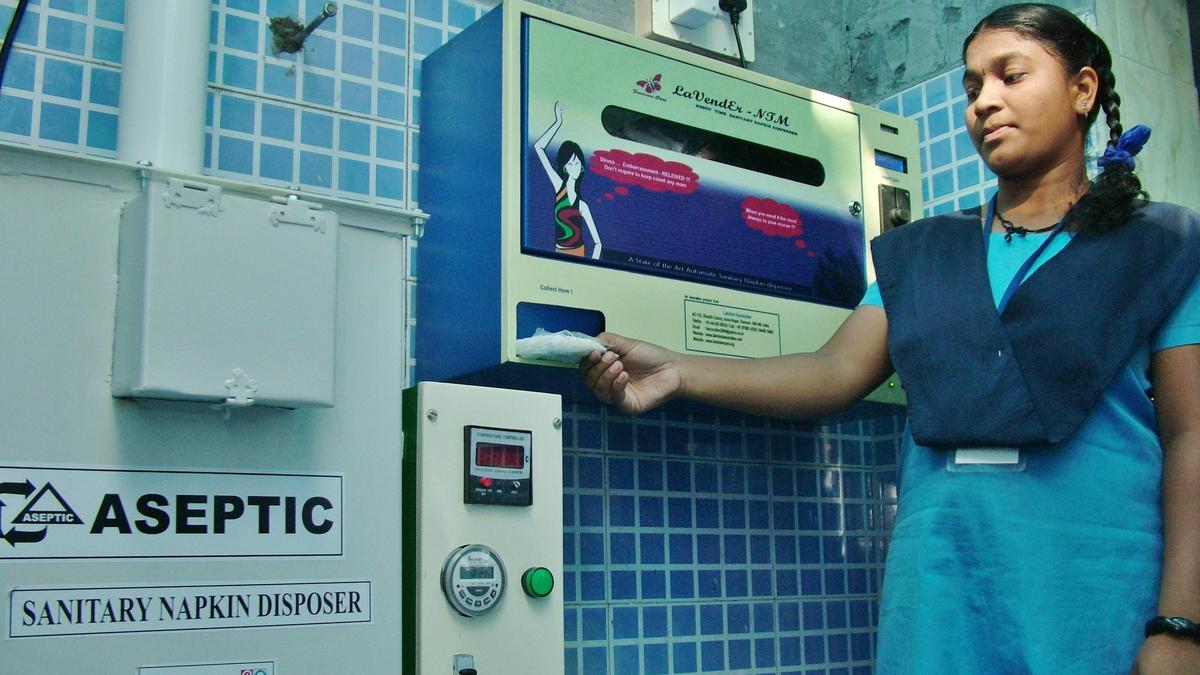

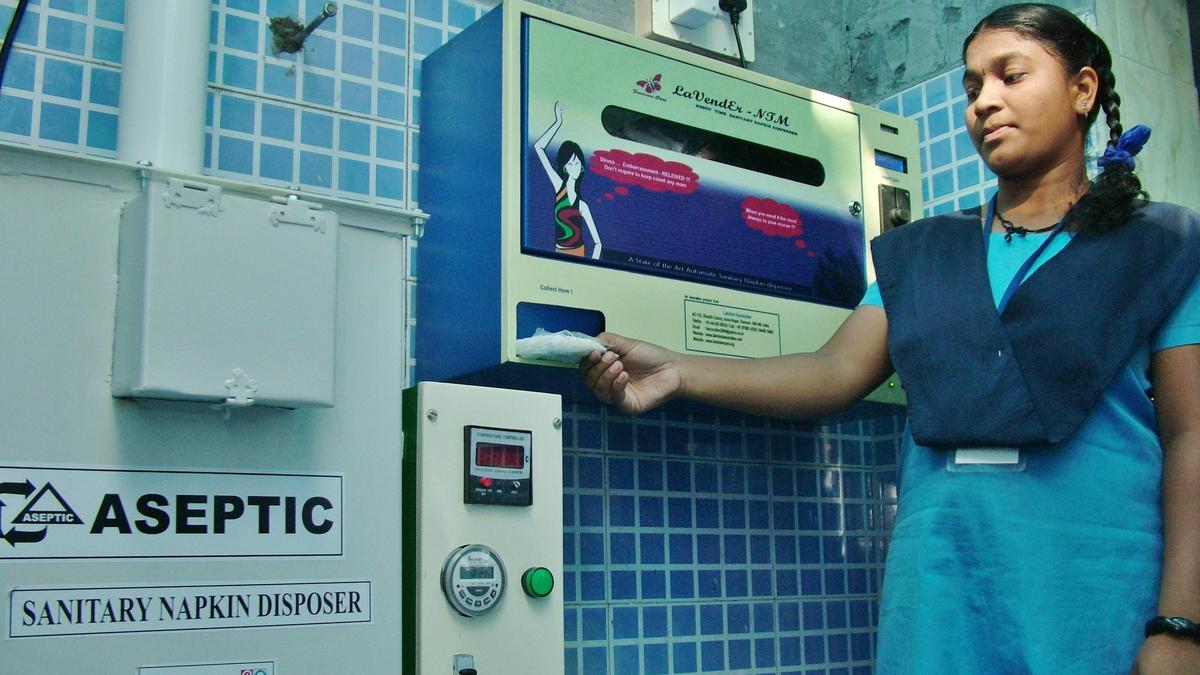

The Shuchi scheme was conceived as a critical intervention to provide free sanitary pads to adolescent girls, particularly those from economically weaker backgrounds. Its primary objective was to reduce school dropouts linked to menstruation, improve attendance, and promote awareness about menstrual hygiene. However, the continued delay in procurement has effectively stalled these goals during a significant portion of the academic year, leaving schools to cope without essential supplies.

Teachers and headmasters across districts say they have received no clear communication on when the sanitary pads will be supplied. In many schools, stocks exhausted months ago, forcing staff to either turn students away or make ad hoc arrangements through donations. The absence of a predictable supply chain, they say, has created confusion and embarrassment, particularly for girls who experience their first menstruation at school.

Administrative Hurdles and the Impact on Students

Officials in the education department have acknowledged procedural delays but maintain that procurement is “in progress.” However, critics argue that such explanations offer little comfort when time is running out and the impact on students is immediate and personal. They point out that menstrual hygiene is not a peripheral issue but a core component of adolescent health and education.

For many students, especially in rural and semi-urban areas, the Shuchi scheme is the only reliable source of sanitary pads. Without it, families often resort to unsafe or unhygienic alternatives, reversing hard-won gains in health awareness. The delay, activists say, is not just administrative but deeply social in its consequences.

The timing of the delay has further intensified concerns. With examinations, annual assessments, and co-curricular activities scheduled in the coming months, uninterrupted school attendance becomes crucial. Educators report that girls are increasingly absent during their menstrual cycles, particularly in higher classes where academic pressure is intense. Some students choose to stay home for two or three days every month, losing valuable instructional time and falling behind their peers. Teachers fear that repeated absences could cumulatively affect performance and confidence, especially among first-generation learners.

Broader Social and Health Implications

Public health experts stress that menstrual hygiene management is inseparable from broader health outcomes. Lack of access to sanitary pads increases the risk of infections, reproductive health issues, and long-term complications. The Shuchi scheme was designed precisely to prevent such outcomes by ensuring safe and consistent access. Delays in procurement, they warn, create gaps that expose adolescents to preventable health risks, undermining public health objectives.

Activists working on gender and education issues say the delay reflects a recurring pattern where schemes aimed at girls and women are treated as secondary priorities. While infrastructure projects and textbook procurement often follow strict timelines, welfare measures linked to dignity and bodily autonomy frequently face procedural inertia. This, they argue, sends an implicit message that menstrual health is negotiable rather than essential.

Within schools, the emotional impact on students is palpable. Counsellors and teachers say girls hesitate to ask for help when sanitary pads are unavailable, fearing stigma or judgment. For younger students, particularly those experiencing menstruation for the first time, the absence of institutional support can be traumatic. The Shuchi scheme was meant to provide reassurance that schools are safe and supportive spaces; its absence erodes that sense of security.

Parents, especially mothers, have voiced frustration at parent-teacher meetings. Many say they assumed the government scheme would cover basic needs, allowing them to allocate limited household resources elsewhere. The delay has forced families to stretch already tight budgets or make difficult choices, particularly in households with more than one adolescent girl.

Officials familiar with the procurement process say delays are linked to tendering issues, pricing negotiations, and quality compliance requirements. While these processes are necessary, critics argue that the government should have anticipated timelines and initiated procurement well before the academic year began. The lack of contingency planning, they say, has resulted in a predictable crisis.

Education department officials insist that once procurement is completed, distribution will be expedited. However, school administrators question how effective such late distribution will be. With only four months remaining, they argue, even a rapid rollout cannot compensate for months of missed support. The question, they say, is not just about delivery but about accountability for the delay.

Women’s rights groups have demanded transparency in the procurement process, including clear timelines and public disclosure of reasons for delay. They argue that openness is essential to rebuild trust and ensure that similar lapses do not recur in future academic years. Some groups have also called for decentralised procurement models that allow districts or schools to source pads locally in emergencies.

The delay has also sparked debate on whether menstrual hygiene schemes should be integrated more deeply into school health programmes rather than treated as standalone welfare initiatives. Experts suggest that stronger institutional integration could ensure better monitoring, accountability, and continuity, reducing the likelihood of disruptions.

From a policy perspective, the situation highlights the gap between intent and execution. The Shuchi scheme, when implemented effectively, has been widely praised for its positive impact on attendance and awareness. The current delay threatens to overshadow those achievements, reinforcing scepticism about the State’s ability to sustain long-term welfare commitments.

Students themselves, though rarely heard in policy discussions, bear the brunt of the consequences. Some senior students have quietly pooled money to buy pads for classmates, while others rely on sympathetic teachers. While these acts reflect solidarity, activists stress that they should not be necessary in a system designed to provide universal support.

As the academic year enters its final stretch, pressure is mounting on the government to act swiftly. Educationists argue that even a partial rollout would be better than continued inaction, provided it reaches the most vulnerable schools first. They stress that delays cannot be justified indefinitely when the impact is so immediate and human.

Ultimately, critics say, the Shuchi scheme delay is a reminder that welfare policies are judged not by announcements but by timely delivery. For adolescent girls navigating school, health, and social expectations, access to sanitary pads is not a luxury or an add-on. It is a basic requirement for dignity, continuity, and equality in education. Whether the government can still salvage the scheme’s promise in the remaining months will shape not only this academic year, but also public confidence in future commitments to girls’ education and health.

Ultimately, critics say, the Shuchi scheme delay is a reminder that welfare policies are judged not by announcements but by timely delivery. For adolescent girls navigating school, health, and social expectations, access to sanitary pads is not a luxury or an add-on. It is a basic requirement for dignity, continuity, and equality in education. Whether the government can still salvage the scheme’s promise in the remaining months will shape not only this academic year, but also public confidence in future commitments to girls’ education and health.

Follow: Karnataka Government

Also read: Home | Channel 6 Network – Latest News, Breaking Updates: Politics, Business, Tech & More