One year after a group of Maoists surrendered before the Karnataka government, hopes of rehabilitation, dignity, and reintegration remain largely unrealised, according to former cadres and rights groups. Despite assurances made at the time of surrender, many say promised benefits such as housing support, employment opportunities, and educational assistance have yet to materialise, leaving them in a state of uncertainty and disillusionment. The delay has raised questions about the effectiveness of surrender and rehabilitation policies and the State’s commitment to long-term conflict resolution.

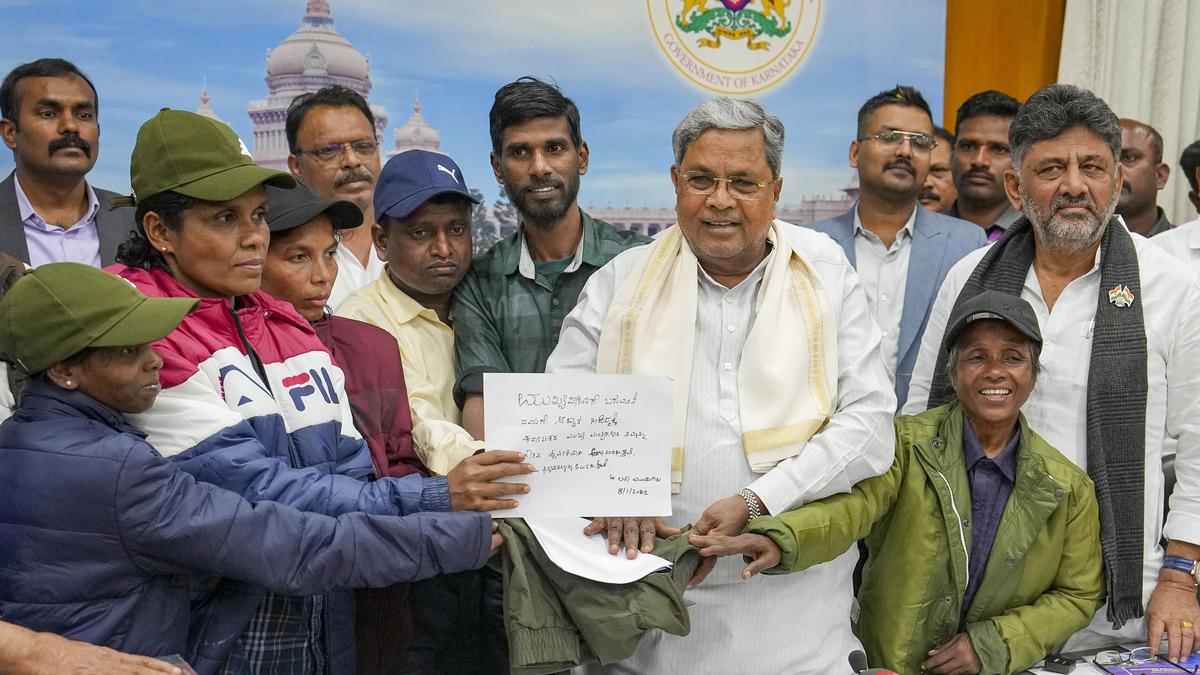

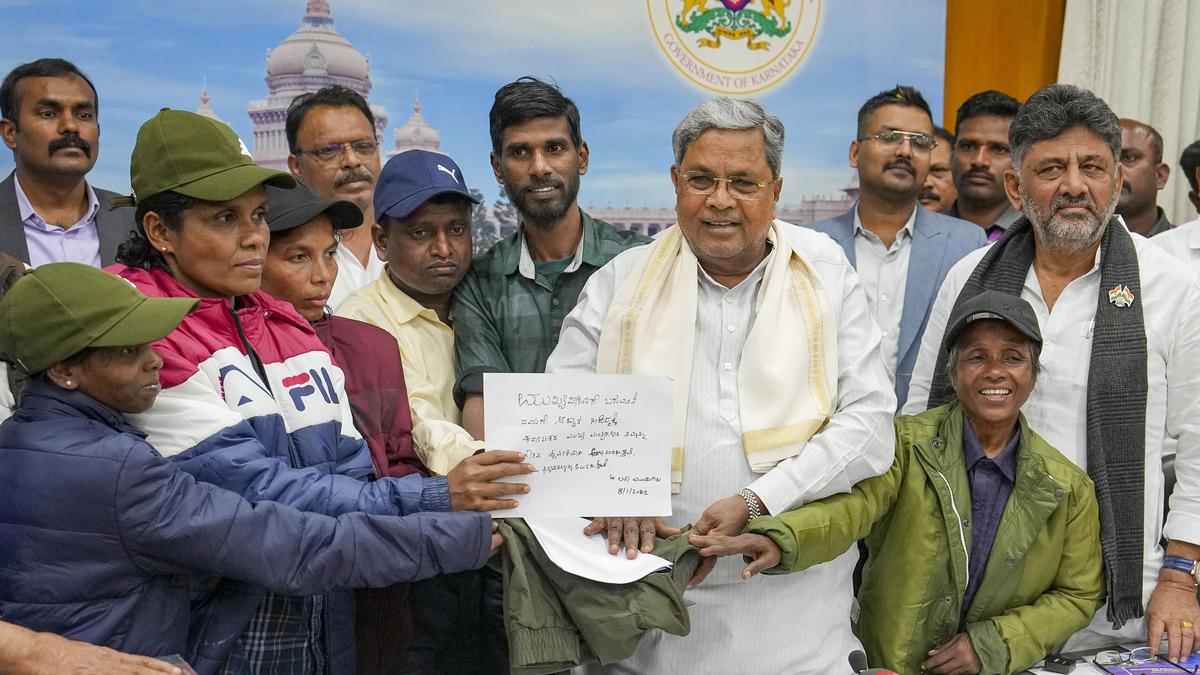

The surrendered Maoists, most of whom laid down arms in districts affected by left-wing extremism, had come forward following appeals from the government that emphasised a humane approach and a chance to rejoin mainstream society. At public surrender ceremonies, officials had highlighted rehabilitation packages as evidence of the State’s willingness to prioritise dialogue and development over prolonged conflict. A year later, however, several beneficiaries claim that the gap between promise and delivery has widened.

Many of the surrendered individuals are currently living in temporary arrangements, dependent on limited stipends or support from civil society organisations. Some say they have received initial financial assistance but have seen no progress beyond that. For others, even basic documentation required to access welfare schemes remains pending, trapping them in bureaucratic limbo.

Observers point out that the delay has also exposed gaps in policy design, particularly the absence of a strong monitoring mechanism after surrender. While the initial act of laying down arms is documented and publicised, follow-up remains largely invisible. Former officials familiar with rehabilitation frameworks say that without periodic reviews at the State level, district administrations tend to treat surrendered cadres as low-priority cases. This, they argue, turns rehabilitation into a symbolic gesture rather than a sustained administrative responsibility, weakening the very foundation of surrender-based peace strategies.

The issue has renewed debate on whether rehabilitation packages are adequately funded and protected from budgetary fluctuations. Rights groups claim that funds earmarked for surrendered Maoists are often absorbed into broader welfare heads, making tracking difficult. In years of fiscal pressure, these allocations are among the first to be delayed. They argue that unless rehabilitation funds are ring-fenced and time-bound, surrendered individuals will continue to face uncertainty, regardless of the government in power.

There is also growing concern about how the lack of progress is being perceived in Maoist-affected regions. Community leaders say that when surrendered cadres struggle visibly, it sends a discouraging message to those still living in forested interiors under insurgent influence. Instead of showcasing reintegration as a viable alternative, the current situation risks reinforcing narratives of mistrust towards the State. This, they warn, could complicate outreach efforts by security forces and administrators working to reduce extremism through dialogue.

As another year unfolds, the question confronting the Karnataka government is not merely administrative but moral and strategic. Rehabilitation is the final, decisive step that converts surrender into lasting peace. Without it, surrender remains incomplete. For the former Maoists waiting for housing, jobs, and dignity, the delay is not an abstract policy failure but a daily reality. How swiftly and sincerely the State responds now may determine whether surrender continues to be seen as a doorway to the mainstream or a promise deferred too long.

Rights activists working closely with surrendered cadres argue that delays in rehabilitation undermine trust in the surrender policy itself. They warn that when assurances are not honoured in a timely manner, it weakens the credibility of the State and discourages others from choosing the path of surrender. Rehabilitation, they stress, is not merely a welfare measure but a strategic component of peace-building.

Officials, meanwhile, attribute the delays to procedural hurdles, inter-departmental coordination issues, and the need for verification. They insist that the government remains committed to fulfilling its promises but acknowledge that implementation has been slower than anticipated. Critics counter that such explanations offer little comfort to those waiting for tangible change in their lives.

Several surrendered Maoists have reportedly approached district administrations seeking clarity on timelines. While some officers have expressed sympathy, concrete outcomes remain elusive. This uncertainty has deepened anxiety among families, particularly children, whose education and stability depend on timely support.

The issue has also attracted political attention, with opposition parties questioning the government’s sincerity. They argue that the administration has focused more on the optics of surrender events than on sustained rehabilitation. Ruling party leaders, however, maintain that the process is ongoing and caution against politicising a sensitive matter.

The broader context of the issue lies in Karnataka’s long-standing struggle with left-wing extremism in certain forested and tribal regions. Over the years, surrender policies have been promoted as a humane alternative to armed confrontation. Success depends not only on encouraging surrender but also on ensuring that those who lay down arms are given a viable future.

Rehabilitation, Bureaucracy, and the Human Cost of Delay

The rehabilitation package announced for surrendered Maoists typically includes financial assistance, housing support, vocational training, and educational benefits for children. In theory, these measures are designed to address both immediate needs and long-term reintegration. In practice, however, implementation often involves multiple departments, from home affairs to social welfare, creating layers of complexity.

Former cadres say the lack of coordination has resulted in repeated visits to government offices without resolution. Some report being asked to submit the same documents multiple times, while others say they have received conflicting information from different officials. This experience, they argue, reinforces feelings of marginalisation that initially pushed them towards insurgency.

Activists note that many surrendered Maoists come from tribal or economically marginalised backgrounds. Navigating bureaucratic systems without assistance can be daunting, particularly for those with limited formal education. They argue that the State must provide dedicated support teams to guide individuals through the rehabilitation process.

Mental health concerns have also surfaced. Transitioning from a life of conflict to civilian existence is emotionally demanding, and prolonged uncertainty exacerbates stress. Counsellors working with surrendered cadres report signs of anxiety, depression, and loss of confidence, particularly among those who feel abandoned after surrendering.

Officials acknowledge that rehabilitation is a complex process but stress that security considerations also play a role. Verification of identities, assessment of criminal cases, and coordination with law enforcement agencies are cited as necessary steps. Critics, however, argue that security checks should not become a pretext for indefinite delay.

The absence of stable employment has emerged as a critical issue. While vocational training was promised, many say such programmes have yet to begin. Without livelihoods, surrendered individuals remain economically vulnerable, increasing the risk of social isolation and exploitation.

Families of surrendered Maoists have also borne the brunt of delays. Spouses and children face stigma in their communities, and without visible state support, reintegration becomes even harder. Rights groups warn that failure to address these challenges could have intergenerational consequences.

District-level officials contend that progress varies by region, with some areas moving faster than others. They argue that local administrative capacity and availability of resources influence outcomes. Nonetheless, the lack of a uniform timeline has fuelled perceptions of neglect.

Trust, Policy Credibility, and the Road Ahead

The unfulfilled demands of surrendered Maoists raise broader questions about the credibility of surrender policies as instruments of conflict resolution. Experts argue that rehabilitation must be treated as an investment in peace rather than a discretionary welfare measure. When promises are delayed or diluted, the message sent to insurgents and affected communities is one of uncertainty.

Security analysts warn that ineffective rehabilitation could undermine counter-insurgency efforts. Surrender policies rely heavily on trust, and any erosion of confidence could discourage others from coming forward. In extreme cases, it may even push individuals back towards underground networks, undoing years of effort.

Civil society organisations have called for a comprehensive review of rehabilitation mechanisms. They suggest appointing nodal officers at the district level, setting clear timelines, and ensuring transparency in fund allocation. Regular public reporting, they argue, could help build accountability.

The State government has indicated that it is examining ways to streamline the process. Officials have spoken of digital tracking systems and inter-departmental coordination committees. While these proposals signal intent, critics emphasise that immediate relief is needed alongside long-term reforms.

Political leaders have urged the administration to honour its commitments without delay. They argue that rehabilitation is not just a moral obligation but a constitutional responsibility towards citizens who have chosen to re-enter the democratic fold.

For the surrendered Maoists themselves, patience is wearing thin. Many say they surrendered in good faith, trusting the State’s assurances. Each passing month without progress, they argue, deepens disillusionment and uncertainty about their future.

The situation has also drawn attention to the need for post-surrender monitoring and support. Experts suggest that rehabilitation should include mentoring, community integration programmes, and continuous engagement rather than one-time assistance.

As Karnataka reflects on a year since the surrender, the gap between policy intent and lived reality remains stark. The challenge now is to translate assurances into action, restoring faith in a process meant to replace conflict with coexistence. Whether the State can do so will shape not only the lives of surrendered Maoists but the broader narrative of peace and reconciliation in affected regions.

Follow: Karnataka Government

Also read: Home | Channel 6 Network – Latest News, Breaking Updates: Politics, Business, Tech & More