A long-running dispute surrounding properties linked to legendary taxidermist Edwin Joubert Van Ingen has taken a new turn, with his nephew proposing that the contested properties in Mysuru and Wayanad be put to community use. Framing the suggestion as an effort to honour both family legacy and public interest, the proposal seeks to move the debate beyond ownership claims and legal contention, towards a resolution rooted in collective benefit and historical responsibility.

The proposal has also reopened conversations about ethical engagement with legacies rooted in colonial-era practices. While Van Ingen’s work is widely admired for technical excellence, contemporary debates around taxidermy, wildlife conservation and historical context add layers of complexity to how such heritage is interpreted today. Scholars argue that community-oriented spaces could provide room for nuanced narratives, acknowledging both craftsmanship and changing values, rather than presenting an uncritical celebration.

In Wayanad, local voices have highlighted the potential for the disputed property to support region-specific needs, such as environmental education, tribal heritage documentation or sustainable tourism initiatives. Residents and activists say that if managed sensitively, the site could become a platform for local knowledge and participation, rather than an externally imposed project disconnected from the area’s social fabric.

There is also growing interest from academic institutions, which see opportunities for interdisciplinary research linked to the Van Ingen legacy. Departments working on museum studies, conservation science and history have indicated that access to such sites could support field-based learning and archival work. Formal partnerships, experts suggest, could ensure that community use is backed by academic rigour and long-term sustainability.

As the dialogue evolves, much will depend on whether stakeholders can move from symbolic proposals to concrete action. The nephew’s suggestion has shifted the tone of the debate, but translating intent into practice will require patience, legal clarity and genuine collaboration. Whether this moment marks a turning point or remains a missed opportunity will shape how the Van Ingen properties are remembered in years to come.

The properties in question are closely associated with Van Ingen, whose name is inseparable from the history of taxidermy in India. For decades, the Van Ingen firm in Mysuru was globally renowned, producing museum-quality work that found its way into prestigious collections and institutions. Over time, however, questions over ownership, inheritance and usage rights of certain properties linked to the family have led to prolonged disputes, particularly concerning sites in Mysuru and Wayanad.

In this context, the nephew’s intervention has been viewed as an attempt to de-escalate tensions and introduce a socially constructive perspective. He has suggested that instead of remaining locked in legal battles or lying unused, the properties could be repurposed for community-oriented activities such as cultural centres, museums, educational spaces or conservation-related initiatives. According to him, such an approach would align more closely with the spirit of Van Ingen’s life and work.

Observers note that disputes over heritage-linked properties often become emotionally charged, blending legal complexity with questions of memory, identity and moral ownership. By advocating community use, the nephew appears to be appealing not only to legal stakeholders but also to public sentiment, positioning the properties as shared cultural assets rather than purely private holdings.

The suggestion has sparked renewed discussion among historians, conservationists and local residents, many of whom have long argued that the Van Ingen legacy deserves careful preservation rather than fragmentation through prolonged disputes. They see potential in transforming contested spaces into sites that educate, commemorate and serve the public, while also respecting the sensitivities of the family.

At the same time, the proposal raises questions about feasibility, governance and consent. Any move towards community use would require agreement among stakeholders, clarity on legal status and a well-defined management structure. Still, many see the suggestion as a rare opening for dialogue in a dispute that has otherwise remained entrenched.

A Legacy Rooted in Craft, Conservation and Controversy

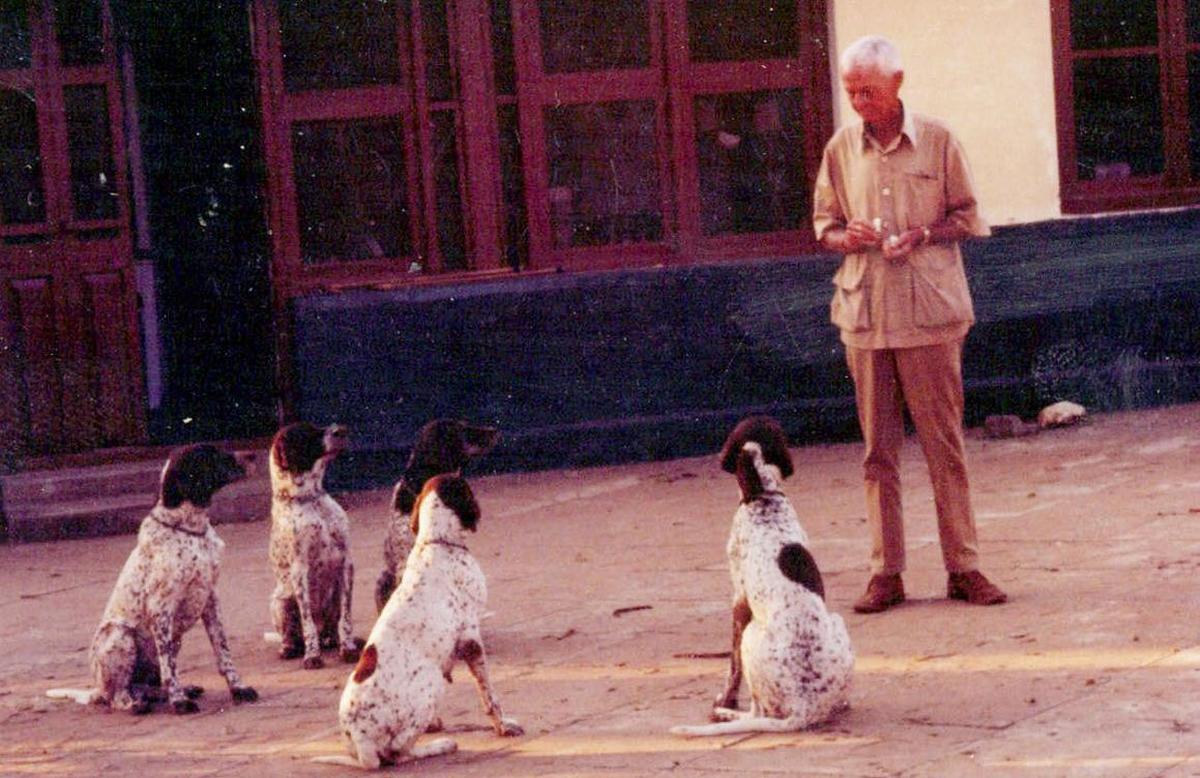

Edwin Joubert Van Ingen occupies a unique place in India’s cultural and natural history. Trained in Europe, he established his taxidermy practice in Mysuru in the early twentieth century, at a time when princely patronage and colonial scientific interest intersected. His work, known for anatomical precision and lifelike presentation, became synonymous with excellence in the field.

The Van Ingen studio in Mysuru functioned not merely as a workshop but as a space of learning and experimentation. Over generations, it trained artisans and assistants who contributed to the development of taxidermy as both a scientific and artistic practice in India. The firm’s output included specimens for museums, educational institutions and private collections, many of which continue to be displayed today.

However, the very prominence of the Van Ingen name has also complicated matters of inheritance and ownership. As the original practice declined and family members dispersed, properties associated with the legacy became subject to competing claims. In Mysuru, questions arose over how certain buildings and land parcels linked to the studio should be treated, particularly given their historical significance. In Wayanad, similar disputes emerged over properties believed to have been part of the family’s extended holdings.

Legal proceedings and administrative interventions over the years have left the status of these properties unclear. In some cases, restrictions on alteration or sale have been imposed due to heritage considerations. In others, prolonged litigation has resulted in neglect, with buildings falling into disrepair and land remaining unused. Local residents have often expressed concern that valuable heritage spaces are being lost to inertia.

The nephew’s proposal must be understood against this backdrop. By suggesting community use, he is effectively reframing the question from “who owns” to “who benefits.” Supporters argue that this shift reflects a broader trend in heritage discourse, where the social value of historic properties is increasingly emphasised alongside legal ownership.

Cultural historians point out that Van Ingen’s work itself straddled the line between private enterprise and public service. While the firm operated commercially, its contributions to museums and educational institutions had enduring public value. Seen in this light, repurposing associated properties for community use could be interpreted as an extension of that legacy.

Yet, critics caution that good intentions alone cannot resolve complex disputes. They argue that any proposal must carefully navigate legal frameworks, respect the rights of all claimants and ensure that community use does not become a vague slogan masking unresolved conflicts. Transparency and inclusive consultation, they stress, will be essential.

Community Use as Resolution: Possibilities and Challenges

The idea of converting disputed heritage properties into community assets is not new, but its implementation is rarely straightforward. In the case of the Van Ingen-linked properties, several models are being discussed by experts and local stakeholders. One possibility is the establishment of a museum or interpretation centre focusing on the history of taxidermy, conservation practices and the Van Ingen contribution. Such a centre could serve educational institutions and tourists alike.

Another suggestion involves creating cultural or research spaces that support biodiversity studies, art conservation or traditional craftsmanship. Given Van Ingen’s association with natural history, conservation-focused initiatives are seen as particularly appropriate. Advocates argue that this would not only preserve the physical structures but also activate them with relevant, meaningful use.

For local communities in Mysuru and Wayanad, access and inclusion are key concerns. Residents have emphasised that any community use must genuinely benefit local people, rather than becoming exclusive or symbolic projects. This could include public access, educational programmes, employment opportunities and partnerships with local institutions.

Administrative challenges, however, loom large. Determining who would manage such facilities, how funding would be secured and how accountability would be ensured are critical questions. Some suggest a trust or foundation model, involving representatives from the family, government agencies, experts and the local community. Others argue for direct public management to avoid conflicts of interest.

Legal clarity remains the biggest hurdle. Without resolution of ownership and usage rights, any proposal risks being stalled or challenged. Legal experts note that courts and authorities may be more receptive to solutions that demonstrate public benefit, but formal agreements would still be necessary to safeguard all parties.

There is also the question of precedent. How this case is handled could influence future disputes involving heritage-linked private properties. A successful community-use model could encourage similar resolutions elsewhere, while a poorly managed attempt could deepen scepticism.

Despite these challenges, the nephew’s proposal has injected a new tone into the conversation. Instead of adversarial positions, it introduces the possibility of collaboration and shared responsibility. For many observers, this shift itself is significant, signalling a willingness to look beyond zero-sum outcomes.

As discussions continue, the fate of the disputed properties remains uncertain. What is clear, however, is that they occupy a space where law, memory and public interest intersect. Whether they become symbols of unresolved conflict or exemplars of inclusive heritage management will depend on how stakeholders respond to this call for community-oriented thinking.

In the end, the question is not merely about land or buildings, but about how society chooses to engage with its past. The Van Ingen legacy, shaped by skill, curiosity and global connection, now faces a moment of reckoning. The proposal for community use offers one possible path forward, asking whether shared heritage can also inspire shared solutions.

Follow: Karnataka Government

Also read: Home | Channel 6 Network – Latest News, Breaking Updates: Politics, Business, Tech & More